Interest in the Internet of Things is booming, in the home, the office and the supply chain. It doesn’t feature any technologies that are revolutionary in themselves — sensors, motors, cameras, servers, internet connectivity, Bluetooth and mobile applications are all standard fare. But assembling them into giant networks that can monitor everything from doorways to energy usage to global supply chains is new. And sometimes it goes wrong. How does that happen, what are the consequences, and what can organizations do to prevent it?

What happens when IoT devices get hacked?

Hacking is one of the biggest concerns for IoT installations. High numbers of low-powered devices make a tempting target with a large, often poorly-secured attack surface.

IoT devices get hacked with horrifying, yet predictable regularity. Anything that can be connected to a network will be attacked eventually; most are attacked within minutes of connection.

Attacks on devices take three main forms:

- Attacks on the device itself, intending to take it over, usually for its spare computing power

- Attacks on the data stream from the device, intending to use the data for various purposes

- Attacks on the network the device is part of, or the core IT network of the organization

Attacks on devices

IoT devices are typically attacked directly within minutes. In 2016, the average device was attacked within six minutes of being connected to a network; in 2019, it was five minutes. Once compromised, IoT devices are used for several purposes. The most common is botnets such as the notorious Mirai botnet, which can be used for crypto mining and DDoS attacks as well as an avenue to steal confidential information. However, botnets are growing in sophistication; a burgeoning market in botnets-for-hire can offer ‘DDoS as a Service,’ but also purvey disinformation and much more.

It’s tempting to think of this kind of attack as more likely to happen to industrial networks, but in fact any IoT device can become part of a botnet. In 2016, a botnet assembled from a globally distributed assortment of security cameras was used to down the servers of a local jewelry store.

‘A total of 25,513 unique IP addresses came within a couple of hours,’ Daniel Cid, CTO of security firm Sucuri, said in a blog post. ‘The source of the attack was concentrated in Taiwan,’ Cid continued, ‘with 24% of the IP addresses [coming from Taiwan]... followed by the USA with 12%, Indonesia with 9%, Mexico with 8%, and Malaysia with 6%.’

Global botnets can be assembled from insecure devices anywhere. Cameras are usually the most poorly-secured devices in business settings, but consumers are increasingly purchasing items that are really IoT devices and treating them like ordinary household appliances. In 2022, the average US household with an internet connection held an average of 16 connected devices. Their owners often don’t do elementary security best practices like changing their device passwords.

‘Some people believe they aren’t important enough to be hacked but we’ve observed how attacks against smart devices intensified during the past year,’ Kaspersky Security Expert Dan Demeter told Digit News.

‘Most of these attacks are preventable, that’s why we advise smart home users to install a reliable security solution, which will help them stay safe.’

The same is true of IoT installations in businesses, and of the Industrial IoT (IIoT). ‘Bad practices such as not changing passwords, or worse, leaving devices installed with factory-default passwords are epidemic in IoT ecosystems,’ says the IoT Security Foundation, ‘which makes it very easy to find administrative access to the device and install IoT botnet malware into it.’ It’s not just end devices like sensors that are vulnerable; there’s been a rise in server botnets in recent years.

Attacks on data

Data stream attacks seek to intercept information flowing around IoT networks and use the data. It might be used to design social engineering attacks by acquiring knowledge about the company or individual users. It may also be used for industrial espionage. Unlike IoT botnets, data streams can’t be ‘owned’ by hackers and used or directed by them, so they’re of less direct value.

IoT data is transferred between devices at the same level on the network (laterally), and between the network and the application layer. Sometimes this data is acquired directly in transit; if it’s sent unencrypted, sniffer technology can be used to simply pick it up from a nearby location. It can also be attacked in other ways; direct eavesdropping on the data stream from a sensor, such as a video camera or audio microphone, is possible with a vulnerability that’s known to exist in about 83 million connected devices.

However, it’s also sometimes picked up from infected devices or from infected applications. Infected devices aren’t always used to construct botnets: sometimes their data streams are stolen instead, often for resale. Here’s a ‘Nest Shop,’ selling data streams from Nest home devices:

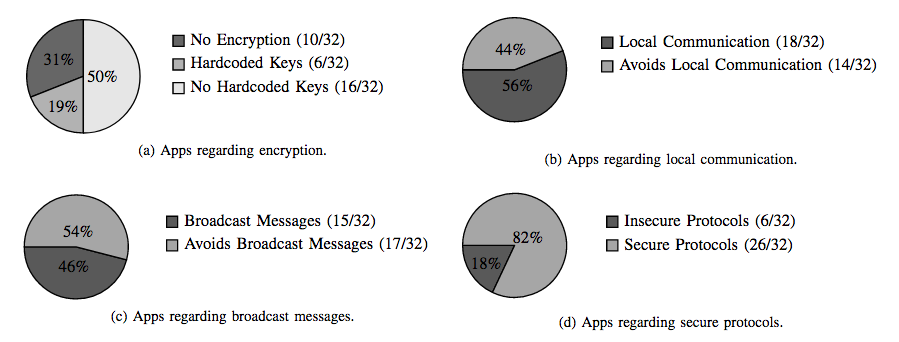

Again, this is about poor security practices. These extend to applications as well as devices and data streams. Researchers at the University of Michigan and Federal University of Pernambuco analyzed 37 of the most popular IoT applications and found the following:

- 31% of these applications had no encryption

- 19% did have encryption, but the keys were encoded and users couldn’t change them

- 50% were vulnerable to known exploits

- 40%-60% used local communication or local broadcast communication protocols

Attacks on networks

Typically, IoT attacks simply exploit whichever link in the chain is weakest. Nest uses cloud-based management, so attackers probe the device. Some networks have secure devices and weakly-protected data streams or unencrypted applications, so attackers turn their attention there. Once compromised, data or access can be sold. But what about attacks on IoT networks themselves?

Attacks on IoT networks are relatively rare, though they are vulnerable to known network attacks such as DDoS and spoofing (this raises the specter of one IoT network being used to DDoS another). What’s more common is using IoT as a gateway to core IT services. In its most ‘classical’ form, this can mean hacking an office security camera, typically the most insecure of any business’ IT assets precisely because it isn’t usually regarded as one, and then using it to steal the business’ financials or customer data or to attack the business with ransomware.

However, this can also be done in the home, where connected devices are also often connected to the ‘core IT’ of home computers and users’ smartphones, with their banking, payment, social and other applications.

Hacks aren’t the only reasons IoT projects fail. Sometimes they fail not because outsiders knock them down, but because they weren’t built well enough to begin with.

What happens when IoT projects and companies fail?

IoT networks rely on everything working together well. We’ve seen what can happen when some technical elements aren’t aligned. But those outcomes are relatively benign compared to what happens when business concerns don’t line up.

Consider the case of Emberlight. Now almost forgotten, Emberlight was once the bright hope of tech-savvy Kickstarter users, who donated $300,000 to the company in 2014 to develop smart light sockets that worked with ordinary lightbulbs. Three years later, Emberlight switched off for good.

Of course, companies and projects sputter out all the time. But Emberlight’s can teach us something. The company shuttered its cloud service when it went out of business, and when it did so, all its smart sockets stopped working. Customers won’t be literally in the dark for long, because regular old fashioned ‘dumb’ light sockets aren’t hard to come by, but it still illustrates the point that an IoT installation can have dependencies beyond itself. Whether it fails because it’s been attacked by hackers, physically damaged in a natural disaster, or because the business unit that owns and operates it has ceased to exist, the repercussions can be serious.

Emberlight’s customers were merely inconvenienced. So were Revolv’s customers, when the company sold out to Nest and pulled the plug on its own cloud service, bricking the smart hubs they’d sold customers in the process. Wink suffered a software glitch that temporarily disabled its products, then its parent company filed for bankruptcy later the same year. If you were one of those affected, it was probably extremely irritating. However, other cases are far more serious.

Second Sight used to make retinal implants to help improve the vision of the visually impaired — ‘bionic eyes.’ However, it’s since discontinued its implant line, and more recently, its support for them, leaving users of the devices literally in the dark without warning. It’s a cautionary tale among several in healthcare, where connected devices come with the same rewards as they do everywhere else — and the same risks, magnified.

There’s the risk that the company will just shut down and leave its users stranded. There’s also the risk of attacks.

Billy Rios of the security firm Whitescope and Jonathan Butts of QED Secure Solutions began studying Medtronic, identifying serious flaws in the security of its smart pacemakers — including the possibility, which they demonstrated, of activating, overloading, or deactivating it remotely from an unauthorized device. After more than two years of talking with Medtronic, they told Wired magazine that they were looking for a more dramatic way to make their point about the device’s vulnerabilities: ‘We were talking about bringing a live pig [to an event] because we have an app where you could kill it from your iPhone remotely.' The same dangers apply to some defibrillators and other devices.

The biggest IoT mishap: failure to launch

Most IoT projects don’t launch, and then go wrong; they go wrong and don’t launch. Crucial obstacles are planning, technical capacity, interoperability, and short-sighted strategic management. In 2017, when about 75% of IoT projects failed at or shortly after launch, Cisco's Australian CTO Kevin Bloch told ZDNET why he thought it happened: ‘Typically, these solutions have been designed to solve a particular societal problem such as lighting or parking. In each case, a complete IT stack needs to be built in support of the solution,’ Bloch explained.

‘Eventually, customers find themselves with multiple siloes from multiple vendors that don't interoperate, are not cybersecure, use different protocols, and generate more complexity at greater cost.’

Even more than security, or any specific technical element, it’s failure to tie the project together at the strategic level that dooms it. In 2019, 70% of IoT projects failed before getting out of pilot; looks like Bloch’s critique is as valid now as it was then.

Who pays the price?

Figuring out who is liable for IoT problems isn’t a simple task. Networks are distributed — and assembled from components supplied by multiple actors; when something goes wrong, it could arise from the interaction of several of those components. Whose fault is it? Who is obliged to fix it? It’s time to get acquainted with federal liability law.

Which is kind of the problem, because there isn’t much federal regulation. If you’re reading this outside the US, it’s likely still relevant if your vendors are stateside, which at least some of them likely are. US states have their own, often-unclear product liability laws. At least, however, when an ordinary product goes wrong somehow, it’s easy to figure out who could be liable. One product, one customer, one retailer, one supplier. IoT installations are not so clear.

If a device is hacked, then used to gain access to the application layer, where data is stolen and used to commit fraud, where does liability lie? The application developer, or the company whose data was stolen, or the device manufacturer? Inside a complex system like an IoT installation, assigning quantifiable roles and identifying the proportions of value and blame rapidly becomes difficult or impossible. There’s little case law, not much regulation and no settled federal law to act as a guide, so companies face being left holding the bag for years if something goes wrong.

For these reasons, it’s even more important than in other spaces to ensure that IoT projects are constructed wisely.

How can AndPlus help?

IoT development and implementation involves careful, strategic planning. Projects do best when there’s someone on hand to consult and guide, asking questions about business fit, the five-year view ahead, and how your IoT project can better serve your overall business goals. They need strategy, but they need the logistics too: which services should you choose? Which OS plays well with which devices? How should your application be structured, how should your network be architected?

At AndPlus, we’ve been helping clients answer these questions since the inception of the IoT. Whether small on-premises networks, highly-distributed installations or major IIoT projects, we’ve developed applications that support business success across multiple verticals.

AndPlus uses the principles of agile software development to structure and build IoT projects with short feedback and iteration loops, meaning we can make data-driven decisions even as we build out two- to three-year roadmaps that let us design not just the best solutions, but the best ways to reach them.

Takeaways

- IoT networks are complex, so assigning value, blame and roles isn’t easy. The whole network has to be capable, secure and adaptable.

- Your IoT network, devices and data will be attacked. It’s certain. So they need to be selected, structured and implemented securely from the ground up.

- IoT vendors aren’t all the same; it’s important to choose network components that won’t have support suddenly withdrawn, while maximally leveraging the provisions of service providers.

- Around three-quarters of IoT projects fail. Correctly-managed and architected ones don’t. But correctly managing, architecting and developing for IoT installations is a complex task that requires a lot of different skillsets, all working together.